How the Tamale Shaped San Francisco

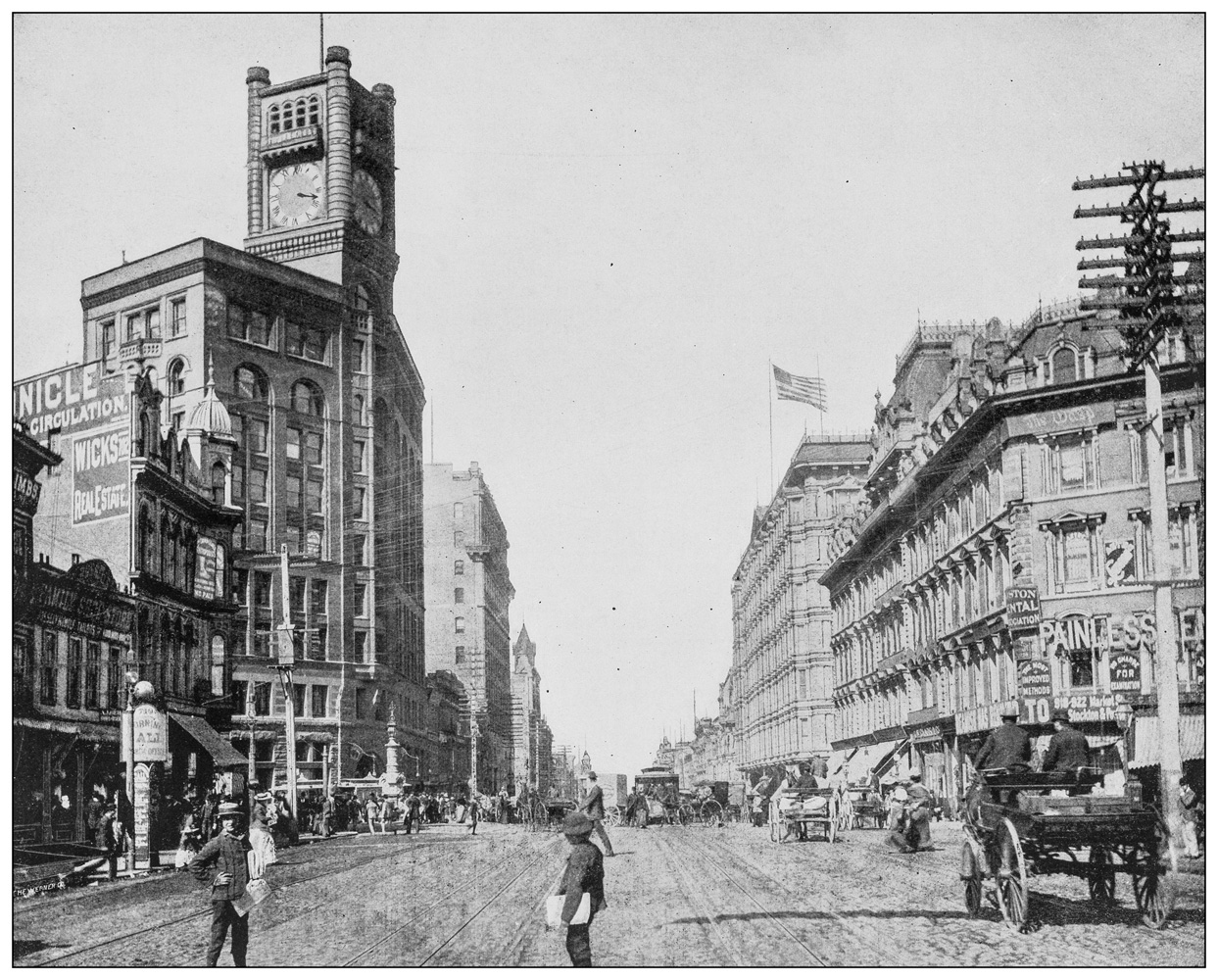

If you were to walk through downtown San Francisco in the 1870s, you’d see wide streets lined with tall, Victorian-style buildings. You’d watch men in top hats and tailored suits alongside women in puffed Italian sleeves and long skirts crossing dust-filled roads. You’d hear the creaky wooden wheels of horse-drawn carriages rolling over the hard dirt ground as they made visible tracks through the fallen dust.

You’d also become mesmerized by the scent of warm masa and roasted chicken wafting through the air. Tamales were San Francisco’s original hot and ready street food, sold by vendors throughout the young city once upon a time. Though their popularity has had its fair share of ebbs and flows, today they’re a beloved staple of the street food lineup. So, how exactly did the tamale make its way from Mexico to the street carts of San Francisco?

How the Tamale Landed in San Francisco

It’s more accurate to say that San Francisco landed on the tamale. The land once belonged to Mexico, inhabited by the Californios. These settlers were of Spanish and Mexican descent and made their living trading cattle. The classic meat-stuffed Mexican tamale was a staple in their home kitchens, often with a Mediterranean twist of chopped olives courtesy of the Franciscan missionaries who brought olive trees over from Spain.

When the Mexican-American War ended in 1846, what was once Mexico became America, and the Californios were granted citizenship. But the moment James William Marshall struck gold in 1848, everything changed. In less than two short years, the promise of riches drove the population of this foggy, seaside town from 1,000 inhabitants to a city of more than 25,000 people.

Land value increased as more Anglo-Americans flooded in, and the Californios were pushed out. The first California Assembly reduced them to second-class citizens, stripping them of land and political power. They were subjected to additional taxes and new statutes like the Greaser Act, an anti-vagrancy law that penalized being insufficiently housed, primarily targeting Mexicans and Native Americans.

Building (and Feeding) a City from Scratch

Despite claims of abundant riches, the actual odds of striking it rich in the gold mines were low. This rapid population boom paired with a lack of existing infrastructure caused a dramatic rise in the cost of food, which meant endless opportunities to build a city and furnish it with urban conveniences. So the real money was in selling tools and building supplies, manufacturing jeans for miners (Levi Strauss), and making and selling food.

The majority of the miners arriving were white males, and only eight percent of the new population was made up of women. The men didn’t know how to cook for themselves and were barely getting enough to eat. They mostly lived off of biscuits and sourdough bread, which weren’t suited to the nature of mining because they required ovens and took a lot of time and effort to make.

Fine French restaurants were there for those who could afford them, but there was a need for quick, cheap, and convenient meals for those on miners’ wages. Mexican foods like tortillas and tamales were the perfect sustenance. They could provide a calorie-dense meal for hungry laborers and cooked quickly over a hot fire.

This was the tamale’s moment to shine! Mexican “Tamaleros “ donned traditional sombreros and pantaloons, selling tamales on street corners. The cheap and filling handheld meals were instantly popular among non-white laborers. But due to their poverty, the Californios were snubbed by white miners, and little social or mealtime interaction took place between the Mexicans and the Anglo settlers. Defeating Mexico in the war made Americans, in particular, too prideful to embrace the food culture of their southern neighbors.

This was the tamale’s moment to shine! Mexican “Tamaleros “ donned traditional sombreros and pantaloons, selling tamales on street corners. The cheap and filling handheld meals were instantly popular among non-white laborers. But due to their poverty, the Californios were snubbed by white miners, and little social or mealtime interaction took place between the Mexicans and the Anglo settlers. Defeating Mexico in the war made Americans, in particular, too prideful to embrace the food culture of their southern neighbors.

As a result, the exotic tamale faced a racially-motivated propaganda campaign that presented them as inferior to the fancy French foods the wealthy were eating in restaurants. White settlers, eager to diminish the reputations of the Californios, began to spread rumors that the tamale vendors were unsanitary. To add insult to injury, tamale vendors were fined regularly for their operations.

While tamales remained popular among many immigrants, Americans and Europeans rarely gave Mexican vendors a chance. Instead, they opted for more familiar (but far less convenient, less healthy, and arguably blander) foods. These racist notions caused many low-wage white miners to suffer from malnutrition and hunger.

The Americanization of the Tamale

The tamale remained popular among the Mexican population, but by the early 1890s, opportunistic white businessmen began to usurp their businesses. In 1892, Robert H. Putnam opened *The California Chicken Tamale Co*. But instead of hiring Mexican workers, he hired immigrants from Greece, Chile, Lithuania, Brazil, Italy, and Poland, dressing them in uniforms of white linen to lend the operation a crisp, “sanitary” perception. They wore round stovepipe hats and distributed warm tamales from steam pails. Putnam soon expanded to cities across the country and the tamale craze spread. In 1894, the magazine Good Housekeeping even printed a home recipe for tamales, introducing them as “the dish is sold in the streets of San Francisco.”

The Industrialization of the Tamale

The Americanization of “exotic” foods as a business model was quickly imitated by entrepreneurs across the US. But a corn husk shortage in 1895 slowed things down dramatically, and many vendors were forced to close. Seeing this as an opportunity to promote their canning businesses, American businessmen decried street vendors as dangerous and unsanitary. Since cans would eliminate the need for hard-to-find corn husks, they began suggesting that industrial canning and the inspection that came with it made tamales safer to eat.

Charles H. Workman opened the W.G.M. Canning Company in 1900, which signaled the final blow for the tamale street vendor. Earning the post-mortem nickname “Tamale King,” Workman patented a special can lining that allowed workers to stuff tin cans with a can-shaped layer of masa and then fill them with meat. He quickly derailed the competition, increasing production from 300 tamales a day in 1900 to 140,000 per day in 1913.

The Complicated Legacy of the Tamale

Laws regulating who could sell street food in the late 1800s persisted for over a century, making factories the intermediaries between maker and consumer. As America became more reliant on convenience foods starting in the 1950s and 60s, tamales were something you either made at home, ordered in a Mexican restaurant, or bought in the frozen food section of a grocery store.

The connection between immigration, street vendors, and racial discrimination can’t be ignored because it has persisted for so long. After Mexican vendors were sanitation-shamed in the late 1800s, sending the tamale business off the streets and into factories, the early 1900s saw the tamale trade thrive once again. This time, in the hands of Sikh and Afghan immigrants. But by 1917, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors passed a statute that specifically banned the sale of street tamales.

Meanwhile, non-white citizenship became an ever more complicated affair, often being revoked from hard-working immigrants in order to remove them as economic competitors. Even when citizenship requirements loosened for non-whites during WWII (namely because America wanted to avoid comparisons to the Nazis), regulatory hurdles kept immigrant food vendors from hitting the streets again for decades.

A Tale of Two Tamales

Taking a walk through San Francisco nowadays, much like in the 1870s, you can still latch on to the toasty scent of warm tamales in the air. You can grab a burrito, a taco, or a tamale from a street vendor on just about any corner of the city. But the streetside legacy of the tamale didn’t come full circle until the early 2000s.

The resurgence of street food in San Francisco started getting noticed around 2009. An article in the SFGate described both legal and illegal operations popping up around the city. The most famous vendor, in an ironic nod to the roots of the city, was Virginia Ramos, a.k.a The Tamale Lady. Ramos emigrated to the city in 1980, and through house cleaning and tamale trading, she put five children through college.

Ramos was a beloved staple of the after-bar scene, but when the San Francisco Environmental Health Department got wind of her side hustle in 2013, they warned the bars she set up in front of that they would be fined for allowing an illegal vendor to set up shop near their business. The community then pooled funds to get her a legal brick-and-mortar business, but she died before the doors opened. Her story is documented in the 2018 short film Our Lady of Tamale.

The legal landscape is still murky, despite a nationwide surge in the popularity of street food. San Francisco was recently named one of the five most difficult cities in America to start a food truck business. The existing laws have been flagged for how aspiring entrepreneurs, big and small, are vetted differently when it comes to licensing. LA Times columnist Gustavo Arrellano wrote in a 2022 article, “When high-end chefs do all this, they get love from the press and praise from hipsters. When working-class Latinos do it? They get code enforcement called on them — and politicians figuring out how to crack down on street food even further.”

An Icon of Immigration History

From the Gold Rush to today, this street food battle doesn’t seem to be fizzling away. Thankfully, food lovers, talented cooks, and equity advocates have come up with workarounds that are making the process easier for immigrants and aspiring entrepreneurs to get into the food business.

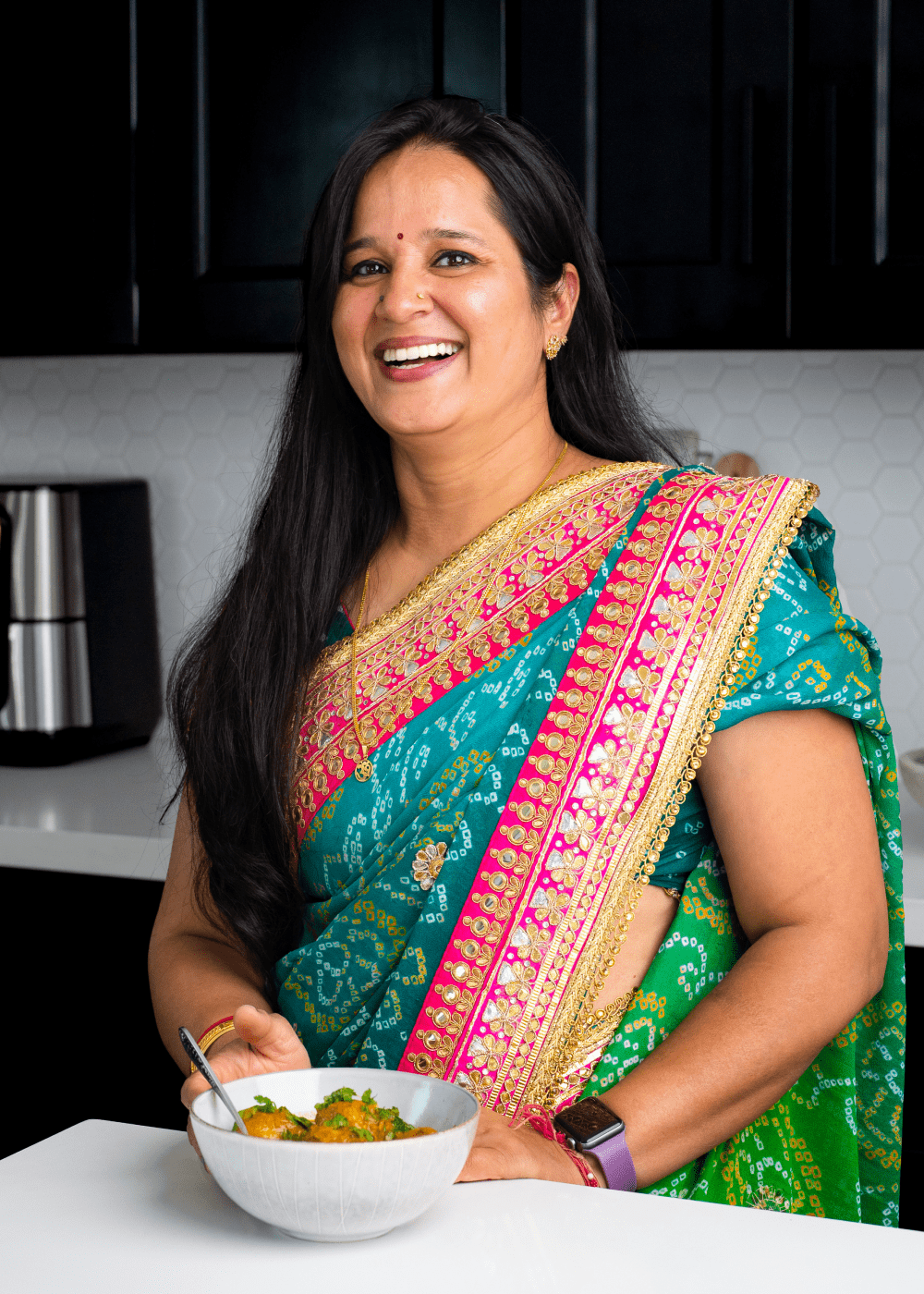

Platforms like Shef are making the food economy more widely accessible, particularly for immigrants, refugees, women, and people of color. We connect local, food safety-certified cooks with customers in their community, helping them earn a meaningful income by selling homemade dishes. Nonprofits like La Cocina help these same communities access commercial kitchens where they can learn the business side and navigate the tricky legal waters with more ease and support.

The San Francisco tamale is loaded with more than melty cheese, spicy jalapeños, and shredded chicken. It’s a literal bite of history, taking us back to the very origin of the city itself. It’s the story of immigration, equity, and hungry entrepreneurs. Above all, the tamale is a symbol of perseverance. So, the next time you unwrap a warm husk and sink your teeth into that soft bundle, remember that over a century of boundaries were broken through in order for it to end up in your hands. The tamale isn’t just street food. It’s a verifiable icon of San Francisco’s culinary history.