The History of Sourdough Bread

There’s no mistaking the signature tart flavor and crusty crunch of a thick slice of sourdough bread. It’s the perfect platform for any sandwich, the ideal dipper for a brothy bowl of soup, and the ultimate BFF for your butter board. But what do we really know about everyone’s favorite slow-bread? Read on to learn about its origins, arrival in San Francisco, and how to order a loaf on Shef.

What is Sourdough Bread?

Sourdough is a naturally leavened bread, which means it rises on its own through a process of fermentation. Rather than tossing in a packet of commercial yeast, you’ll need a “starter” to make it rise naturally. If you were bitten by the baker’s bug during the pandemic, you know it’s not a bread for beginners. It’s an artisan loaf that requires time, patience, skill, and attention to detail.

A starter is a mixture of flour and water that’s left to ferment. Wild yeasts are infused and over time, microorganisms and good bacteria, like Lactobacillus, are born. These bacteria digest the carbohydrates in the flour, starting the fermentation process. Bubbles of carbon dioxide force the dough to rise as the gas gets trapped. Lactic acid gives sourdough its characteristic chewy texture and sour, tangy flavor.

The Ancient History of Sourdough Bread

Sourdough is the oldest type of leavened bread, dating back to at least 1500 BC. The ancient Egyptians are credited with the “accident,” as dough was supposedly left out in the open and exposed to wild yeast spores that were likely carried over from beer production. Back then, both bread and beer were dietary staples and often produced in the same physical spaces.

The result was magical! The bread was light and airy rather than dense and overly chewy thanks to the fermentation process forcing the dough to puff up. It tasted better, too, with heightened complexity of sweet and tart flavors. Over time, bakers experimented with various wild yeasts, keeping specific, favored cultures alive by feeding them with a little more flour each day to keep the fermentation process active.

Sourdough moved through the ancient world, and more and more bakers altered it and made slight improvements every time it landed somewhere new. It went from Egypt to Greece, and then to ancient Rome. Pliny the Elder, a Roman historian, wrote a recipe for sourdough starter in 77 AD that called for flour, wild grapes, water, and millet.

When the French were introduced to the sourdough starter, their existing penchant for bread making took it to a new level. Recipes from the 17th century mention a starter that is fed three times and allowed to rise three times before it’s added to the dough. Flavor was of utmost importance, and bakers had no problems waiting for more complexity to develop over a multi-day rise.

Why is San Francisco Famous for Sourdough Bread?

Like so many culinary imports to the United States, sourdough arrived thanks to the economic boom presented by the California Gold Rush of 1849. Master French bakers brought their starters from France; most notably, the Boudin family. They opened a bakery, and their bread was instantly popular. Their prized “mother” was heroically saved by Louise Boudin during the Great San Francisco Earthquake of 1906. You can still find the Boudin Bakery and its original starter alive and well in San Francisco today.

Sourdough was so popular that miners and prospectors used to carry their starters with them everywhere. Called “sponges,” they tried to keep them warm and active through the winter months. It allowed them the ability to make delicious, leavened bread on cast iron over the fire at campsites, earning them the nickname “Sour Doughs.”

The Fall and Rise of Sourdough

Prior to the 19th century, all leavened bread was made using naturally occurring yeast. Effectively, all bread that wasn’t flatbread was technically sourdough. Then, just 150 years ago, commercially produced yeasts arrived (see photo above.)

These new commercial yeasts, most commonly derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, made bread rise faster. The cultural values were changing too, with producers favoring a more profitable product with less attention to flavor. In 1910, labor-related bills were passed that restricted late night working hours. Commercial breads were less interesting to eat, but they were much faster to make, so they became the main loaves you’d find in shops.

It wasn’t until the 1980s that the tide turned again. People began favoring the more ancient breadmaking process, noting the unique, holey texture and flavor of sourdough when compared to the loaves people were buying in grocery stores.

Sourdough, Today

Today, sourdough continues to be favored by many, and it’s not uncommon to see lines of people outside bakeries waiting for a loaf to take home. The pandemic also peaked a renewed interest in home baking, and sourdough in particular experienced a resurgence in popularity worldwide.

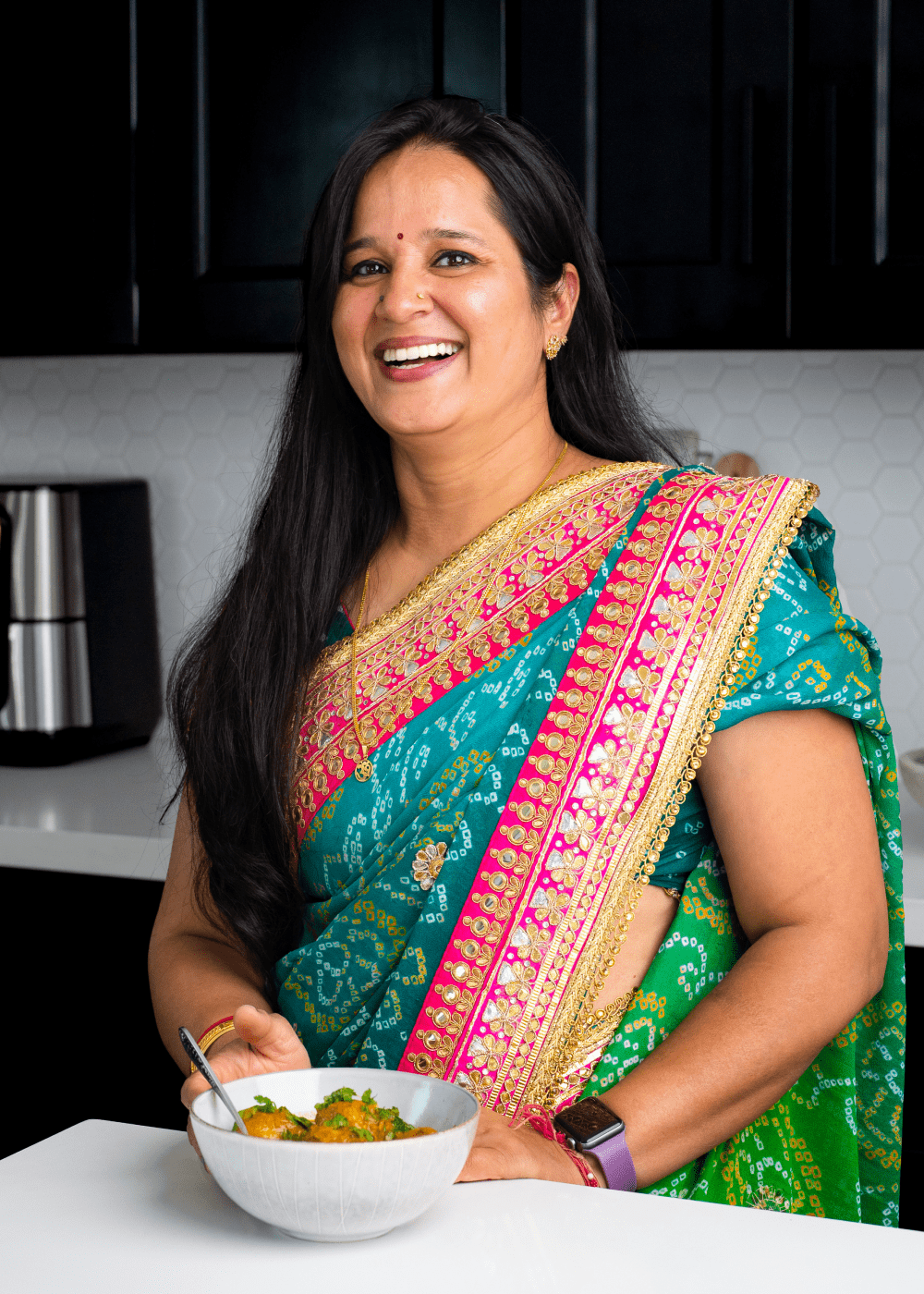

Once people started going back to work, the appreciation for sourdough remained, but few had the time to feed starters and knead their dough throughout the week. Home bakers, like Shef Joan in San Francisco, have helped busy bread lovers get their fix. She makes classic sourdough as well as unique and seasonal loaves like Pecan Pumpkin, Chocolate Cranberry Walnut, Everything Bagel Sourdough, and Jalapeño Cheddar. So, if you don’t have time time or patience to make it at home, you can get one of these creative and delicious sourdough loaves delivered to your door.